A good campaign isn’t just a series of unconnected events and rallies. It must be based on a coherent idea of what’s going to be achieved and how to achieve it. For a campaign to succeed there must be a set of goals; an understanding of the campaign’s impact upon your organization, constituents and allies; and knowledge of the opponents, targets, tactics and timelines. Although campaign planning may seem a little daunting at first, don't worry – it can be among the most interesting and intellectually engaging parts of organizing. And, be willing to invest time at the beginning of your campaign to produce a detailed campaign plan. The thoughtfulness and consideration that goes into your campaign plan at the onset will likely be a major determining factor of the campaign's eventual success. Most importantly, have fun with it – campaign planning is a unique and exciting process that too few people ever experience. “If at first you don’t succeed,

escalate, escalate, escalate again.” This is a brief overview of what your campaign might look like. Basically, most campaigns have 7 parts: ..........1. Research These different parts do not necessarily take place consecutively. You might start with some recruitment, do some research, then choose your campaign. Planning and strategizing are crucial. They require your group to lay out clear goals, identify resources and allies, identify the decision makers who can give you what you want, and plan your tactics. Recruitment, education and coalition building are the means to build support and power to win your campaign. Interaction with the target is a nice way of saying that you are asking for what you want. The target is the person/people who can give you what you want. This step really tests the strength of the group, yet it pertains to the area that is most familiar to groups: tactics. You may be able to walk into the president’s office, sit down and say "Bob, I think it’s time we get rid of disposables in the cafeteria," and get the response, "Yes Sir." If that’s the case, well, either you’re lucky or you just gave the school a library. If you’re like most campus activists, you’d be stopped at the president’s secretary, which means you need to do something a little more exciting. Interaction with the target does not need to be confrontational, but don’t be afraid of confrontation. Finally, you win or regroup (a nice way of saying that you lost and need to reevaluate your goals). At each turning point or after a campaign is won, it is critical for your group to evaluate your actions and decide ways to do the next tactic or campaign better. - top -

Before you can develop a good campaign, you should understand power. Although power is often abused and used to oppress others, don’t be fooled: power is “value-neutral” and organizing is a form of building it. Although we may lack money or institutional power, students can often (through our use of organizing) mobilize people power. Organizing is about leveling the playing field: sharing power with students, the community, and the public. Basically, organizing is about democracy. In your campaign, you should assess the power your members and allies have, compare it with your opponents’, and choose an area where you can over-power them and win. - top - Before you try to organize students at your school, you should first consult with faculty, alumni, and other students who’ve formed progressive organizations there. Find out what worked and what has failed. Don’t repeat the mistakes of others; learn from the past. Do your research and find out what precedents may exist: campaigns at your university similar to what you’re thinking of. For instance, if you’re considering running a divestment campaign, it would be useful to know if any divestment efforts had been successful in the past (such as Apartheid or Tobacco). - top - Once your group has chosen a campaign, it's time to get down to the nitty-gritty details of planning it. Never begin a campaign without setting clear goals.

A goal is a concrete, measurable end that you want to reach. You need to be able to refer back to it later and answer the question: “Have we won?” Your goals should be defined as specifically as possible, and divided into long-range, medium range and short-range goals. ..........• Long-Term

Goals: These are far-reaching goals that you hope to achieve

eventually. Your current campaign is a step towards reaching these

goals. Long-term goals are important because they keep your group

focused on the deeper and more systemic change you seek while you’re

addressing immediate issues. For instance: ..........• Long range:

Forcing Dow to accept its responsibilities in Bhopal Notice that your long-range goal is not the objective of your current campaign. However the medium-range goal that you’ve set, which is the objective of your campaign, will help build pressure for Dow to agree to your longer-range goal. There could be various and multiple short-term goals for this campaign (e.g., collect 10,000 petition signatures in support of divestment, elicit a supportive editorial from the campus newspaper, etc.). The specific short-term or tactical goals that you set will depend on your strategy. The nature of these goals will become clearer after we discuss strategy and tactics in the following sections. - top - Once you have a clear sense of your goals, it’s critical that your group assesses its organizational strengths and weaknesses. What resources are currently available to your group? What resources are you lacking? In this assessment, be certain to consider all types of resources - money, volunteers, facilities, skills, time, connections, reputation, and others. Also ask what internal problems, if any, need to be fixed before you can move forward. This is also the time to identify your friends and enemies – those allies you should reach out to assist with the campaign and those opponents who may attempt to hinder your campaign efforts. To identify your allies, you should answer the following questions: To identify your opponents, you should answer the following

questions: Try not to limit yourself to "traditional" allies and opponents. For instance, on campus, traditional allies of progressive causes include the environmental club, the anti-sweatshop group, the LGBT organization, and others. Examine carefully how the issue you are working on may affect other groups of people and reach out to them. Be specific. - top - The campaign should also build your organization. How can this campaign create new leaders and strengthen the ones you have? How can it bring in new members? How can it involve members at a variety of levels of commitment? You should think about how many people your project could employ. This is especially important when planning for the introductory meeting, since you want new people to get involved. If you don’t involve them, they won’t stick around long. There should be a range of jobs, from light to heavy, to make it easy for new people to get involved without signing their life away. Try to increase each member’s level of commitment over time. - top - The next step is identifying your campaign targets.

A target is the person(s) with the power to give you what you want. You cannot simply pressure the “powers that be” - there must be a person that you’re asking to do something concrete. Even if the power to give you what you want is an institution (e.g., the university or Dow), it’s important to personalize the target. Identify who ultimately makes the decision within that institution or, at least, who has the most influence over it. That individual will be your target. By personalizing the target, you can take advantage of the human responses of decision makers during your campaign - ambition, guilt, fairness, fear, or vanity. These responses don’t exist in institutions as a whole. When attempting to identify your target(s) when planning a

campaign, start by asking the following questions: Once you’ve identified your target, review your organizational resources and those of your allies and determine what influence you may hold over them. You may be able to convince your target to support your position if you have sufficient influence; otherwise, you’ll need to determine how to mobilize the power of your members and allies against the vulnerabilities of the target and pressure him or her to give you what you want. If your group does not have any power or influence over your primary target, you’ll need to identify a secondary target. A secondary target is a person who can influence or has power over the primary target.

To identify secondary targets, ask yourself the following questions: For instance, suppose you’re trying to get the CEO of Wombat Invaders Inc. to stop selling baby formula that turns children into wombats. Even if you can’t influence him or her, stockholders can. Consumers can. The government can. If you’re trying to influence the University President, what about students & faculty? Alumni? Wealthy donors? Because unless you choose your targets strategically, wombats will soon march all over the face of the earth. And no one wants that. - top - You’ve chosen your campaign, defined your goals, and assessed your campaign environment. Now it's time to devise your campaign strategy. Strategy is a systematic set of tactics arranged to influence a specific target towards a specific goal.

It’s critical that you think strategically about your campaign so that you’ll succeed in reaching the goals you want to see fulfilled. When mapping out campaign strategy, you should start by answering

the following questions: Keep your organizational strengths and weaknesses in mind. Don’t bite off more than you can chew (for instance, a mass mailing to alumni if you have $10 in your account) or concentrate your efforts where your organization is weak (for instance, by organizing direct actions without the proper training). Are you a running a majority campaign or minority one? Majority campaigns rely upon educating the majority of people to support you in theory, whether or not they do it explicitly. If you want to maintain mass support you’ll be limited in the tactics you can choose – pouring red paint on the shoes of your college President, for example, is bound to turn some folks off. The alternative is to mobilize a small group of really committed people and rely upon the neutrality or apathy of the masses. A minority could exert substantial pressure by occupying a building, sitting in trees threatened with logging, or holding weekly protests which cause your target to negotiate (and/or give-in) just to get rid of you. Generally majority campaigns are most successful. If you do decide to use controversial tactics in a majority campaign, make sure that folks understand what you’re doing and why it’s important. - top - Now that you have a sensible strategy in mind, you can choose your tactics. Tactics serve your campaign plan by pressuring your target(s) to give you what you want. Acting out or implementing tactics are often people's favorite part of a campaign. Unfortunately, as a result, many people neglect the previous campaign planning steps and jump right to this point. Not surprisingly, these campaign efforts often end up becoming a disjointed collection of tactics lacking strategic coherency and a real sense of how they’re working towards achieving the central goal. Tactics should: Consider the following when determining your tactics: You need to be clear on these things if your tactic is to have any long-range impact. Is your rally to influence the public or the administration? Will the media you get from it raise awareness for an upcoming vote? Why should the President care about 100 students on her front lawn anyway? Follow-up is especially important. Are you demanding a meeting and setting a deadline or just making some noise and walking away? What will you do if they do nothing? If you develop a goal for each tactical action, it’ll be easier to assess your progress. For instance, rather than stating that you’ll generate phone calls to your university president and leaving it at that, state that you’ll generate 300 calls. Tactical goals are really a type of short-term campaign goal and, thus, can serve as benchmarks to measure the progress of your campaign effort and to generate excitement among your membership at achieving victories. Your group should celebrate these victories, however small they might be, to encourage optimism and enthusiasm within the organization. Innovation Tactic innovation has been a great boon to student movements whether it was sitting-in at lunch counters to fight segregation, draft-card burning, going on strike (as millions of students did in May 1970), divesting from South African apartheid, occupying buildings (Ontario students in 1997), sitting-in to oppose sweatshops, or putting on a play (Vagina Monologues). Generally each new tactic, if it’s a good idea, leads to a surge in activism. You can also innovate in your forms of education. Perhaps you might want to focus on a different aspect of the issue every week, so that you appeal to different groups of people, your message stays interesting, and you overwhelm your opposition and apathetic students with reasons for why your issue matters. - top - Now that you know what you want and who’s going to give it to you, it’s necessary to develop your campaign message. A campaign message or slogan is a short (10 words or less), clear, and persuasive statement that is used in all campaign communications (verbal or written) to deliver a quick and consistent description of your campaign effort to the media, the public, potential allies, and others. Campaign messages are very useful to ensure that the primary target of your campaign is receiving a clear and consistent demand regardless of the source of that communication. Keep in mind the old saying that when you become physically ill at having to repeat the campaign message for the umpteenth time, only then is it finally starting to seep into the public's consciousness. - top - Sometimes projects drag on with no real sense of progress. To avoid this, draw up a timeline. This is simply a schedule for when you expect to get things done. This is especially important when preparing for things with definite dates, like rallies and talks. Think carefully about all things that need to get done and when they need to get done by. At your meetings, decide on a reasonable amount of time for assignments to get done. The items on the timeline should be specific. For instance: ..........• 2/7 - Assign someone

to make a poster for the Toxic Buffet and get it printed. Look at the student calendar before you set a timeline. Be aware of vacations, holidays, weather, major sports events, and so on. Try to avoid conflict with other people’s meetings, events, and exams. Also consider the student power cycle. Student Power Cycle At the beginning of the year student power is very low, because of the long summer break and because of the loss of students who have graduated, dropped-out, gone abroad, or changed their personal priorities. However, students are in a good mood and ready to join new activities or to reinvigorate their involvement in past ones. Thus this is an excellent time to start a new group, launch a new campaign, or reinvigorate an old one. Student power will quickly build due to enthusiasm and good weather reaching a peak right before mid-term exams. It will decline during exams and afterwards during the fall break. However after this, student power will swiftly recover and reach a peak that is as high or greater than the first fall peak. A week or so before final exams, student power will sharply decline and remain at negligible levels over winter break. In the winter (or spring) semester, student power will not recover as quickly as during the fall because of the cold weather which discourages outdoor activism and the lesser enthusiasm of the returning students whose winter vacation was shorter than that of the summer. However, as student activists have been educating, agitating, and recruiting for several months, as the semester progresses and the weather improves, student power will hit a strong peak before midterm exams. It will decline sharply during spring break, but return to achieve its highest potential of the entire school year. If you want to maximize your chance of success, you should plan to have your largest mobilizations during this peak in March or April. Finally, student power will decline as final exams and summer approach. This is a general approximation of how student power changes over time. Other holidays (such as Thanksgiving and Easter) may have a significant negative impact. Also sports games or school-specific events (like a Parents or Siblings weekend) can also hurt. Students are affected differently by this cycle, for instance graduate students who do not have course work may still be able to work very hard at the end of the semester. Conclusions In the case of a very hard campaign, you might want to find a secondary goal that will put you on the path to your real goal and to try and achieve this secondary goal in March/April. Or if the campaign is not so hard, you might strive for your secondary goal in October or November, and the real win in March/April. If the campaign is easy, you could try to win it all in one semester. Although you don’t have to structure your timeline to perfectly fit this energy cycle, you should keep it in mind and use it when it could help you. - top - The last component of campaign planning is to manage your resources. Funding and volunteers will probably be your biggest concern. Quite simply, after you’ve determined what your goals, strategies, and tactics will be, calculate how much the campaign will cost your group and develop a campaign budget. Lastly, just like with funding, you should assess how many volunteers you’ll need to help you run this campaign. Even if your current membership is large enough to run your campaign, make one of your organizational goals to recruit more members. Also, consider how you can use this campaign as a way to train your members in new skills and build group leadership. - top - Generally, campaigns go through several phases:

A simplistic strategy for winning a campaign would be to divide your time into two phases. During the first phase you’d tell everyone about the problem (education), and in the second you‘d engage in action that would mobilize everyone - and then you’d win. However, you’ll need a more complex strategy to maximize your chances of success – one that recognizes the need to integrate action and education into the same phases. First you should do initial research about the issue so that you have your facts straight (note: you should continue to do research as the campaign progresses). Keep in mind that while you may start your campaign by focusing on research and education, if you don’t move quickly to a combined action and education phase, you’ll risk demobilizing your supporters. Many people will rightfully suspect that a group with a purely educational campaign that relies upon making moral or rational appeals to a powerful elite is deluding itself! These folks will either join another organization that has a better strategy or stay away from activism. Thus from the beginning of your campaign, you’ll want it to be clear that you’ll engage in a campaign that will rock your school and/or community with ACTION. Your movement will be mobilizing hundreds of people, building and demonstrating power, and that’s why you have a good chance of winning.

The powerful tonic for success combines action with education. You have action to mobilize people, to demonstrate your power, to keep things exciting, and to show that you mean “business”. Meanwhile you constantly incorporate education into your campaign. At first your educational goal is simply to demonstrate that there is a PROBLEM to a modest sized group of students. Bad stuff is going down and you have a realistic means of tackling it. You should get enough supporters so that you can engage in major actions, such as rallies, without being embarrassed by a lack of attendance. As your campaign progresses, you’ll be able to expand the reach of your educational activities from beyond targeting the usual suspects (progressive students and organizations) to finding ways of involving students who might normally be moderate, apathetic, or even conservative. If your issue is being debated all over the student newspaper, on the walls and sidewalks of your school with posters and chalk, by speakers, and in leafleting, protests, and other actions – then students who’d normally avoid getting involved will become interested. In addition, as your campaign progresses and grows your members will be better prepared to educate others. They shall be able to provide both a simple argument that will convince most people why you’re correct, as well as a lengthier analysis of how this issue is connected to other issues and how your goal is a small step in a larger movement to create lasting change. It’ll become obvious to everyone on campus that your group really knows its stuff!

On the other hand, there are times when you may not want to enter a cycle of endless escalation. In some situations it can be strategic to take a step back. For instance, if it appears that your target is granting serious consideration to your demands, you might want to reduce your level of confrontation and give them a chance to change their position. You don’t want to make it extremely difficult for them to grant your demands. At the same time, you don’t want to completely withdraw pressure – as they may just be stalling for time.

Winning Losing If you decide to stick with the same campaign, then you should analyze what needs to be done better. Be careful to avoid non-strategic escalation and martyring yourself for this cause. You may find this particularly appealing if you are about to graduate and you feel that this is the last chance for your movement to succeed. However, a tiny group of people engaging in extremely radical action may alienate your supporters and destroy any chance your campaign has of success. If you cannot convince the upcoming leaders/continuing members in your group to continue with the campaign, it may be for the best and they may know something that you do not. On the other hand, if your group decides to continue with the campaign there are several things to consider. Perhaps you timed your campaign to peak too early and should have waited for March or April to pull off your largest action. Or it is likely that you will need to build a larger coalition to bring in more people to support you and then to mobilize these people in a mass, low risk action like a traditional rally, and also to engage in higher-risk forms of activity like a sit-in. Your strategy may have failed because you failed to organize enough people (a question of “width”) or because you failed to get them involved enough (a question of “depth”). To solve the width issue you might need a systematic education campaign that could mean doing presentations to as many classes as possible (Indiana University No Sweat did presentations to thousands of students before they met with their administration), canvassing the dorms to talk to people individually, holding meetings in each dorm or on each floor of each dorm (students at Macalester did this for their anti-sweatshop campaign). To solve the depth issue you might want to create a direct action planning group to organize a sit-in or other dramatic action at the peak of the student power cycle. Even just leaking the threat of such an event may be enough to push your target to agree to your demands (For instance by collecting a list of students who would be willing to engage in a sit-in). During the anti-sweatshop movement due to the large number of sit-ins at other schools, administrators knew that if they did not cooperate with student activists at their school that their student activists might do a sit-in. - top -

- top - ..........• Cover

Story: A Fun Shared Vision Exercise by Idealist on Campus

|

The international student campaign to hold Dow

accountable for Bhopal, and its other toxic legacies around the world.

For more information about the campaign, or for problems regarding this

website, contact Ryan

Bodanyi, the Coordinator of Students for Bhopal.

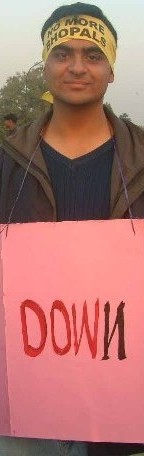

WE

ALL LIVE  IN

BHOPAL

IN

BHOPAL

"The year 2003 was a special year in the history of the campaign for justice in Bhopal. It was the year when student and youth supporters from at least 30 campuses in the US and India took action against Dow Chemical or in support of the demands of the Bhopal survivors. As we enter the 20th year of the unfolding Bhopal disaster, we can, with your support, convey to Dow Chemical that the fight for justice in Bhopal is getting stronger and will continue till justice is done. We look forward to your continued support and good wishes, and hope that our joint struggle will pave the way for a just world free of the abuse of corporate power."

Signed/ Rasheeda Bi, Champa Devi Shukla

Bhopal Gas Affected Women Stationery Employees Union

International Campaign for Justice in Bhopal

This is what the www.studentsforbhopal.org site looked like in early 2008. For more recent information, please visit www.bhopal.net.