Dow claims that it has no liability for the Bhopal disaster. Not to put too fine a point on it, but they’re liars.

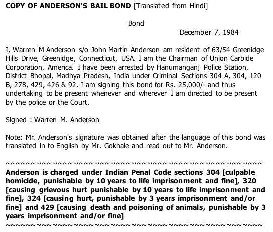

Key Outstanding Liabilities Two court cases are pending: one civil, heard in the Southern District federal court in New York; the other criminal, heard before the Chief Judicial Magistrate’s court in Bhopal. The civil case - which is unrelated to the disaster itself - was filed in United States federal court in 1999 by Bhopal residents against Union Carbide. When it fled India after Bhopal, Carbide left tons of chemical wastes behind, and these have poisoned the groundwater and thousands of Bhopal residents. The civil case seeks a comprehensive cleanup of the contaminated site and the properties around the factory, and compensation and medical monitoring for those poisoned by Carbide’s chemical waste. The lawsuit, Bano v. Union Carbide, has survived four motions to dismiss, and has been reinstated twice by the 2nd Circuit Court of Appeals. The case is currently in the discovery process, and will soon proceed to trial. The criminal case - which is related to the 1984 Bhopal disaster – was originally filed in 1987, and reinstated in 1991. Both Warren Anderson, the former CEO of Union Carbide, and the Union Carbide Corporation itself face criminal charges in India of “culpable homicide” (or manslaughter). Both Anderson and Carbide have repeatedly ignored summons to appear in India for trial, and are officially considered “absconders” (fugitives from justice) by the Indian Government. While Anderson, if extradited and convicted, would face ten years in prison, Carbide faces a fine which has no upper limit. - top - In March 1985, through the Bhopal Gas Leak Disaster (Processing of Claims) Act, the Indian Government arrogated to itself the sole powers to represent the victims in the civil litigation against Union Carbide. It then filed a $3 billion compensation suit on behalf of the victims in US federal court, but the case was sent to Indian courts in May 1986 on grounds of forum non-convenience, under the condition that Union Carbide would submit to the jurisdiction of Indian courts. Carbide’s lawyers devised a plan to delay all legal proceedings in order to squeeze the Indian government into accepting a low settlement. It contested the legitimacy of courts it had asked to be tried before. It pleaded to have ‘illiterate’ victims’ claims denied. It threatened to summon every individual survivor and appeal all Indian decisions in US courts. It denied it was a multinational. It claimed the gas was not ultra-hazardous. It blamed an unnamed saboteur. It appealed court orders for humanitarian relief, while professing its concern for the victims. Their first settlement offer was a paltry $100 million dollars, less than half the company’s liability insurance cover. By 1989, Carbide had spent at least $50 million on legal fees alone. How much they spent on PR companies such as Burson Marsteller, who they hired from Dec. 20 1984, has not been disclosed. It wasn’t until 1989 that a settlement was reached between

Carbide and the Indian Government – one made without the consultation

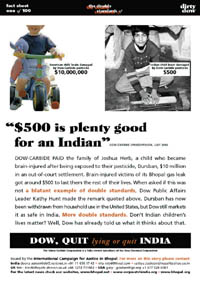

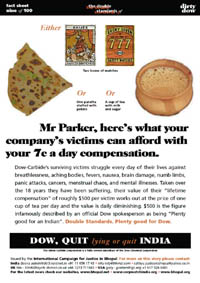

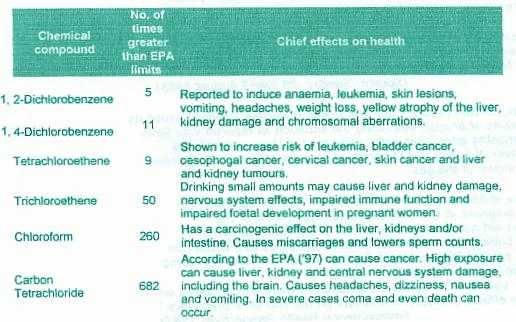

or consent of the survivors themselves. The victims were Many survivors found the settlement insulting. Indeed it was. It awarded them an average of 7 cents a day – the cost of a cup of tea – for a lifetime of unimaginable suffering. At Union Carbide, by contrast, “restructuring” - or asset stripping - in the immediate aftermath of Bhopal landed its managers and major shareholders huge windfalls in stock payments and golden parachutes. It paid only $200 million (or 43 cents a share) of its own money to settle the world’s largest peacetime massacre. In fact its annual report described 1989, the year of the settlement, as its ‘best financial year on record’. After having waited five long years for compensation, the Bhopal victims nevertheless filed suit to overturn the settlement in a case that went all the way to the Indian Supreme Court. Citing inaccurate statistics for the number of dead and injured victims, the court ruled in 1991 that the settlement amount would stand, simultaneously reinstating the criminal cases against Carbide, its CEO Warren Anderson, and other officials. - top - The Contamination A 1990 study by the Bhopal Group for Information and Action found di- and trichlorobenzenes in water samples taken from wells being used by communities living near the factory fence lines, and phthalates, chlorinated benzenes and aromatic hydrocarbons in the soil samples taken from the SEPs. In 1996, the State Research Laboratory conducted its own tests on water and concluded that the chemical contamination found is “due to chemicals used in the Union Carbide factory that have proven to be extremely harmful for health. Therefore the use of this water for drinking must be stopped immediately.”

In 1999, Greenpeace and Bhopal community groups documented the presence of stockpiles of toxic pesticides (including Sevin and hexachlorocyclohexane) as well as hazardous wastes and contaminated material scattered throughout the factory site. The survey found substantial and, in some locations, severe contamination of land and water supplies with heavy metals and chlorinated chemicals. Samples of groundwater from wells around the site showed high levels of chlorinated chemicals including chloroform and carbon tetrachloride, indicative of long-term contamination. Over the years, the groundwater supplying an estimated 20,000 Bhopal residents has become heavily contaminated by Union Carbide’s toxic by-products. Lead, nickel, copper, chromium, hexachlorocyclohexane and chlorobenzenes were also found in soil samples. Mercury in some sediment samples was found to be between 20,000 and 6 million times the expected levels. According to a 2002 study by the Fact Finding Mission on Bhopal, many of Union Carbide’s most dangerous toxins can now be found in the breast milk of mothers living around the factory. Responsibility

A preliminary study of soil and groundwater pollution inside the plant, conducted in 1989 by Carbide, found plenty to be worried about. Some water samples produced a 100% death rate among fish placed in them. Nevertheless Carbide issued no warning. An internal memo refers to the need for secrecy, suggesting that the information should be kept "for our own understanding". Not only did it fail to warn people living nearby, it vociferously denied that there was a problem and, incredibly, wrote to the Gas Relief Minister criticizing those who were trying to make people aware of the danger, suggesting that they were "mischievous" agitators. Carbide in the US meanwhile tried to portray Bhopal activists and their supporters as "communists" who aimed "to restructure US society into something unrecognizable and probably unworkable". Carbide and Dow later relied on a report from a government organization called NEERI which in 1997 published a report which found that water outside the factory was not contaminated. Consultant Arthur D Little had been appointed in 1989 by Union Carbide US to work privately with NEERI. ADL believed itself to be working with UCC in Danbury, but all reference to UCC was to be deleted. ADL was to pretend to be working with UCIL alone. But a memo of 1993 shows the US Carbide executives in the driving seat. ADL eventually reported back to Carbide suggesting that NEERI had failed to find contamination because its sampling methods were flawed. In particular ADL suggested it was imprudent to claim that local water was safe for drinking and warned that groundwater contamination could happen far more swiftly and seriously than envisaged. ADL was unclear at one point as to whether NEERI was claiming that labourers were or were not exposed to contaminated groundwater. ADL's suggested changes ran to 17 pages, but none of them were incorporated in NEERI's published report, which is what Dow and Carbide still quote, knowing it to be worthless. Carbide’s own documents reveal that they knew for decades that their disposal practices in Bhopal were leading to massive contamination of the soil and groundwater, and that their sole concern was how to evade responsibility and cover it up. Polluter Pays In a June 28, 2004 official letter, the Indian Government has gone so far as to stress that the polluter pays principle applies in this specific case: "Pursuant to the ‘polluter pays’ principle recognized by both the United States and India, Union Carbide should bear all of the financial burden and cost for the purpose of environmental clean up and remediation." The letter was issued in support of Bano v. Union Carbide. The Lawsuit Interestingly, many of the internal Union Carbide documents which reveal the extent of Carbide’s negligence, culpability and naked greed in Bhopal have become public as a result of this lawsuit. In this interview, Raj Sharma, the lead attorney for the Bhopal victims in this case, describes their significance. Many of the key judgments in the case are available here. Dow’s PR/BS Dow has also sought to elude responsibility for a cleanup by shifting the blame. Although the site has always been owned by the State Government of Madhya Pradesh, it was leased by Carbide for its pesticide factory. Carbide returned this lease to the State Government in 1998, but without fulfilling one of its key provisions: that the site be returned in a pristine state. Carbide itself acknowledges this was a condition for the lease in this document. Although polluter pays is the law in India, Dow has argued that the current owner of the land, the Madhya Pradesh government, is responsible for the cleanup. Dow has also argued that the $300 million accrued through interest on Union Carbide’s original 1989 settlement - which the Indian Supreme Court ruled in July 2004 exists solely to compensate the Bhopal victims for the loss of their health, their livelihoods, and their loved ones - should be used to pay for a cleanup, turning the polluter pays principle entirely on its head. In summary, Dow has said both that local government should pay for the clean up AND that gas survivors should pay - the first is in contravention of lawful principle and common sense, while the second contradicts all notions of human decency. Chronology of the Case Selected Press Coverage - top - Responsibility

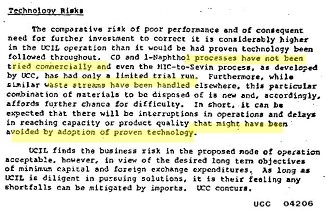

The Indian subsidiary UCIL was majority owned by the US corporation and even relatively minor decisions could not be made without reference to the US. Carbide provided all process designs in Bhopal, which included flow diagrams, material and energy balances, operating manuals and other information necessary for the erection and start up and operation of the plant. It couldn't be any other way: no India-based firm had any experience of MIC/Sevin production whatsoever. This technology exchange from the US to India was formalised in a technical services agreement and UCIL paid for continual know-how and safety audits. Internal Carbide documents also reveal that UCC set up a "design review process", meaning continual review of design by US engineers. Carbide had ample warning that a disaster was imminent. On December 25, 1981, a leak of phosgene killed one worker, Ashraf Khan, at the plant and severely injured two others. On January 9, 1982, twenty five workers were hospitalized as a result of another leak at the plant. During the "safety week" proposed by management to address worker grievances about the Bhopal facility, repeated incidents of such toxic leakage took place and workers took the opportunity to complain directly to the American management officials present. In the wake of these incidents, workers at the plant demanded hazardous duty pay scales commensurate with the fact that they were required to handle hazardous substances. These requests were denied. Yet another leak on October 5, 1982 affected hundreds of nearby residents requiring hospitalization of large numbers of people residing in the communities surrounding the plant. Opposition legislators raised the issue in the State Assembly and the clamor surrounding these incidents culminated in a 1983 motion that urged the state government to force the company to relocate the plant to a less-populated area. Starting in 1982, a local journalist named Rajkumar Keswani had frantically attempted to warn of the dangers posed by the facility. In September of 1982, he wrote an article entitled "Please Save this City." Other articles, written later, bore grimly prophetic titles such as "Bhopal Sitting on Top of a Volcano" and "If You Do Not Understand This You Will Be Wiped Out." Just five months before the tragedy, he wrote his final article: "Bhopal on the Brink of a Disaster." In May 1982, Union Carbide sent a team of U.S. experts to inspect the Bhopal plant as part of its periodic safety audits. This report, which was forwarded to Union Carbide's management in the United States, speaks unequivocally of a "potential for the release of toxic materials" and a consequent "runaway reaction" due to "equipment failure, operating problems, or maintenance problems." In fact, the report goes on to state rather specifically: "Deficiencies in safety valve and instrument maintenance programs.... Filter cleaning operations are performed without slipblinding process. Leaking valves could create serious exposure during this process." In its report, the safety audit team noted a total of 61 hazards, 30 of them major and 11 in the dangerous phosgene/MIC units. It had warned of a “higher potential for a serious incident or more serious consequences if an accident should occur.” Though the report was available to senior U.S. officials of the company, nothing was done. (2) In fact, according to Carbide's internal documents, a major cost-cutting effort (including a reduction of 335 men) was undertaken in 1983, saving the company $1.25 million that year.

Sabotage? Every investigation and analysis not paid for by Carbide concluded causes other than sabotage. The process safety system trumpeted by Carbide included a design modification installed in May 1984 on the say-so of US engineers. This ‘jumper line’, a cheap solution to a maintenance problem, connected a relief valve header to a pressure vent header and enabled water from a routine washing operation to pass between the two, on through a pressure valve, and into MIC storage tank 610. Carbide’s initial investigation agreed that the pressure valve was leaking but declined to mention the jumper line. Carbide itself has cast doubt on the sabotage theory. In Congressional

testimony on March 26, 1985, Union Most damningly of all, although Carbide claims it is certain of the identity of the saboteur “responsible” for the death of 22,000 people, they’ve never publicly revealed his identity. In fact, they’ve been particularly careful to avoid doing so because it would invite a libel suit in which the theory and the facts of the disaster would be open to scrutiny. - top -

If found guilty in criminal proceedings, Union Carbide could be sentenced to a fine which has no upper limit. Such penalties are decided based upon the magnitude of the crime (in this case, the world's worst industrial disaster), the stature and ability of the accused party to pay (Dow-Carbide is the world's largest chemical corporation) and the current state of the victims. Dow Chemical, Carbide’s new owner, has stated publicly that it has no intention of surrendering its subsidiary for trial. In December 2003, Dow’s spokesperson was quoted as saying that “their position on the matter is that the Indian government has no jurisdiction over [them]; therefore, they are not appearing in court.” By refusing to surrender its subsidiary for trial, Dow has placed itself in the legal position of harboring a fugitive. And while Union Carbide no longer has assets in India (which could be seized to compel its appearance for trial), Dow has at least four major subsidiaries in the country. In January 2005, the Chief Judicial Magistrate’s court in Bhopal sent a summons to Dow’s US headquarters, asking it to show cause to the court why Dow’s Indian assets shouldn’t be seized to compel Carbide’s appearance for trial.

The Case Against Warren Anderson As both Chairman of the Board and Chief Executive Officer, Anderson was directly involved, approved and ratified the double standards in design, safety and operations by which Union Carbide imposed at UCIL inferior and inherently dangerous conditions compared with those it chose to establish at its Institute, West Virginia factory. Anderson was personally aware of and involved in the economy drive of Union Carbide's "Bhopal Task Force" to salvage the plant's financial viability. (7) 1982 May: Union Carbide inspection team indicated that the plant at Bhopal, India was unsafe. The report of the Tyson safety audit team This report, which was forwarded to Union Carbide's management in the United States, speaks unequivocally of a "potential for the release of toxic materials" and a consequent "runaway reaction" due to "equipment failure, operating problems, or maintenance problems." The safety audit team also noted a total of 61 hazards, at least 30 of which were major and 11 of which were specifically identified as hazards in the MIC/ phosgene units. 1984 September: An internal Union Carbide memo warned of a "runaway reaction that could cause a catastrophic failure of the storage tanks holding the poisonous [MIC] gas" at the Institute, West Virginia plant. The memo was released in January 1985 by U.S. Representative Henry Waxman (D-CA), Chairman of the House Health and the Environment Subcommittee.

There is prima facie evidence that Anderson knew or should have known about safety conditions in the Bhopal plant and failed to take remedial action before the disaster occurred. Carbide policy states that the CEO is to be notified whenever a serious personal injury or fatality to a Carbide worker occurs. Anderson was informed or should have known about Ashraf Khan’s 1982 death at the Bhopal plant from a gas leak; the response was to send the above-mentioned safety audit team to Bhopal, once again with the knowledge of the CEO. The Tyson report was sent to the CEO's office for remedial action, which was not taken. In the wake of the disaster, Anderson flew to Bhopal as a PR stunt. There he was placed under house arrest and charged by the Indian authorities with "culpable homicide" (manslaughter). Although Anderson was later released on bond and allowed to leave the country, he promised to return to face any criminal proceedings. He did not. After Anderson ignored multiple summons to appear for trial, including one published in the Washington Post (January 1st, 1992), the Indian Government issued an arrest warrant, circulated through Interpol. Anderson then went into hiding. In 2002, Anderson was discovered living a life of luxury in the Hamptons, an exclusive beach resort not far from New York. In May of 2003, the Indian Government requested his extradition, but the request was rejected in July of 2004 by the US Government. India plans to re-submit the request; Anderson is still considered an “absconder” (fugitive from justice) by the Indian Government. If extradited and convicted of the deaths of 20,000 Bhopalis, Anderson faces ten years in prison. Chronology of the Case - top - "If you define 'liability' simply as the ability to lie, than Dow's in liability up to its ears." Like any self-respecting criminal, Dow has prepared its story - neatly fashioned into small soundbites. In November 2000, Dow’s newly elected President and CEO Michael

Parker, in his first media briefing, said: “Clearly, we’re

enormously aware of Bhopal and the fact that particular incident

is associated with Union Lie #1: No Liability Lie #2: The Liability is Carbide’s, not Dow’s Lie #3: No Jurisdiction Lie #4: It's the Government's problem

That’s a rather twisted interpretation of events. The fact is that Eveready Industries India Limited’s “escape” from the site remains unrecognized by the MP Government, and was precipitated by a bureaucratic error. In 1998, EIIL were in the middle of a remediation programme, supervised by the Madhya Pradesh Pollution Control Board (MPPCB). Without communicating its intentions to the MPPCB, the District Industries Centre gave EIIL 10 days to return the lease, citing the fact that they weren’t using the site for industrial purposes any longer. At best the notice was in error, at worst the product of illicit bribery. But EIIL was quick to drop their tools and leave, and when the MPPCB demanded they come back and clean up they refused. There's a telling chronology to the aftermath of this saga this that taken together makes a mockery of Dow's assertion of governmental assumption of responsibility: July 28, 1998: the MP govt issued a statement that, "The State govt will ENSURE safe disposal of the residual Sevin Tar and Napthol Tar from the factory. This will be done in consultation with the NEERI-Nagpur and IICT-Hyderabad." (emphasis added) It is to this statement that Dow perpetually alludes but never actually produces as evidence. The State government isn't saying it will undertake the work itself, just that it will make sure it's done, and with proper professional scrutiny. The work only mentioned only entails surface wastes and does not encompass a comprehensive remediation programme. EIIL itself had paid for the consultation of NEERI and the IICT at the behest of the MPPCB. Feb 1999: The MPPCB, who have been consistent in requiring EIIL/UCIL to remediate the site, write to the site manager CK Hayaran demanding that the work be done as per Management and Waste Handling Rules, 1989, and citing in so many words the polluter pays principle. Oct 19, 2002: The MP govt. announces it will approach the Supreme Court and Centre govt. in order to hold Dow accountable for remediation. (10) February 5, 2003: The MP govt. advises the Central Pollution Control Board to recover costs of clean up from Dow and Eveready Industries India ltd (EIIL). The MP govt. argues that EIIL is still the occupier of the factory site and owner of its contents because of the absence of a formal hand over to the District Industries Center. June 7, 2004: The MP govt. submits a formal letter to the Indian Government in response to a NY court case (Bano v Union Carbide) in which it states that the policy of the government regarding remediation is that “The State Government shall not bear any financial burden for this purpose. The disposal of the chemical waste shall be at the cost of Union Carbide.” June 28, 2004: The Central Government of India submits a formal notice before the Southern District Court of New York (the venue for Bano) in which it states as its official policy that "Pursuant to the ‘polluter pays’ principle recognized by both the United States and India, Union Carbide should bear all of the financial burden and cost for the purpose of environmental clean up and remediation." July 15, 2005: counsel for the Union govt., acting in the MP High Court PIL, seeks a court directive to UCC, Dow and EIIL that they deposit Rs. 100 crores (about $22 million) for site remediation costs.

Shareholders Not Buying It Read an interview with Raj Sharma, the attorney for the Bhopal victims in their New York civil lawsuit, as he describes the significance of Carbide's internal documents. For more about Dow's unreported liabilities, please see Dow Chemical: Risks for Investors, a report by Innovest Stategic Value Advisors. A legal chronology is available here.

(1) According to Union Carbide’s own documentation, obtained through discovery in the New York civil suit. Much of this documentation is available online, at http://www.bhopal.net/poisonpapers.html. See also New Scientist Magazine. “Fresh evidence on Bhopal disaster.” December 2, 2002. Available at: http://www.newscientist.com/news/news.jsp?id=ns99993140. And: The Financial Express. “Global Funds Tell Union Carbide To Settle Bhopal Gas Leak Claims.” Ajay Jain, December 5, 2002. Available at: http://www.financialexpress.com/fe_full_story.php?content_id=23259. (2) See The New York Times. “Union Carbide Had Been Told of Leak Danger.” Philip Shabecoff, January 25, 1985. See also The New York Times. “1982 Report Cited Safety Problems at Plant in India.” Thomas J. Lueck, December 11, 1984. Also: The Christian Science Monitor. “Confidential Indian report blames both US firm and subsidiary for Bhopal disaster.” Mary Anne Weaver, March 26, 1985. And: Time Magazine. “Clouds of Uncertainty; For Bhopal and Union Carbide, the tragedy continues.” Pico Iyer, December 24, 1984. (3) See The New York Times.“Discrepancies are Seen in Bhopal Court Papers.” Stuart Diamond, January 3, 1986. (4) See Section 65 of the Amended Class Action Complaint before the Southern District Court of New York, the full text of which is available at: http://www.bhopal.net/oldsite/amendedplaint.html. (5) Quoted in Chemical and Engineering News, April 8th, 1985. See also The New York Times. “Bhopal Seethes, Pained and Poor 18 Years Later.” Amy Waldman, September 21, 2002. And: New Scientist Magazine. “Fresh evidence on Bhopal disaster.” December 2, 2002. Available at: http://www.newscientist.com/news/news.jsp?id=ns99993140. (6) Anderson and Union Carbide both stand accused of culpable homicide (manslaughter), grievous assault, poisoning and killing of animals and other offenses. See The Washington Post. “India Seeks to Reduce Charge Facing Ex-Union Carbide Boss.” Rama Lakshmi, July 8, 2002. See also the BBC. “India to Extradite Bhopal Boss.” September 6, 2002. Available at: http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/business/2240895.stm. (7) Clemens Work, "Inside story of Union Carbide's India Nightmare," US News & World Report, Jan. 21, 1985. (8) See the Financial Times (London), Sept. 14, 2000. (9) See Dow’s 4th Quarter, 2002, financial summary, available at: http://www.dow.com/financial/pdfs/noreg/161-00587.pdf. By way of comparison, technical guidelines drawn up by Greenpeace scientists in 2002 and handed over to Dow Chemical and the Indian government indicate that a cleanup of Bhopal would cost somewhat over $500 million. See Technical Guidelines for Cleanup at the Union Carbide India Ltd. (UICL) Site in Bhopal, Madhya Pradesh, India. Greenpeace Research Laboratories, University of Exeter, October 2002. Available at: http://www.studentsforbhopal.org/GP.TechGuidelines.pdf. (10) See The Indian Express "MP wants DOW to clean up Carbide mess, State to approach Centre for Supreme Court intervention" by Hartosh Singh Bal, October 19, 2002 (11) See Forbes Magazine. "Dow's Pocket Has a Hole" by Phyllis Bergman, March 31, 2003. Available at: http://www.forbes.com/global/2003/0331/034.html.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The international student campaign to hold Dow

accountable for Bhopal, and its other toxic legacies around the world.

For more information about the campaign, or for problems regarding this

website, contact Ryan

Bodanyi, the Coordinator of Students for Bhopal.

WE

ALL LIVE  IN

BHOPAL

IN

BHOPAL

"The year 2003 was a special year in the history of the campaign for justice in Bhopal. It was the year when student and youth supporters from at least 30 campuses in the US and India took action against Dow Chemical or in support of the demands of the Bhopal survivors. As we enter the 20th year of the unfolding Bhopal disaster, we can, with your support, convey to Dow Chemical that the fight for justice in Bhopal is getting stronger and will continue till justice is done. We look forward to your continued support and good wishes, and hope that our joint struggle will pave the way for a just world free of the abuse of corporate power."

Signed/ Rasheeda Bi, Champa Devi Shukla

Bhopal Gas Affected Women Stationery Employees Union

International Campaign for Justice in Bhopal

This is what the www.studentsforbhopal.org site looked like in early 2008. For more recent information, please visit www.bhopal.net.

Key Outstanding Liabilities

Key Outstanding Liabilities

Union

Carbide factory in Bhopal, while the factory was in operation, massive

amounts of chemicals - including pesticides, solvents, catalysts

and wastes - were routinely

Union

Carbide factory in Bhopal, while the factory was in operation, massive

amounts of chemicals - including pesticides, solvents, catalysts

and wastes - were routinely

fact,

the settlement dealt solely with disaster-related damages sustained

by Bhopal residents, not the environmental liabilities and pollution

associated with the routine operation of the factory. On March 17,

2004 the Second Circuit Court of Appeals

fact,

the settlement dealt solely with disaster-related damages sustained

by Bhopal residents, not the environmental liabilities and pollution

associated with the routine operation of the factory. On March 17,

2004 the Second Circuit Court of Appeals